Many people only discover they have osteoporosis when spinal surgery is being considered. At that point, understandable questions arise: “Will my bones break?”, “Will the screws hold?”, “Is it better not to have surgery?”. This article explains, in clear everyday language, how bone quality affects spine surgery, what can be done to improve it, and what risks and recovery times are realistic.

The information you are about to read is for guidance only and does not replace an individual assessment by a healthcare professional. Every case requires a personalized evaluation.

- Osteoporosis does not always rule out spine surgery, but it does increase the risk of mechanical complications if it is not detected and treated in time.

- A preoperative assessment of bone health (densitometry, blood tests and falls assessment) is just as important as MRI or CT scans.

- In many cases, optimizing bone quality for weeks or months before surgery reduces complications and improves the fixation of screws and prostheses.

- Recovery times are usually a little slower in patients with fragile bones, but with a good rehabilitation plan it is possible to regain an active life.

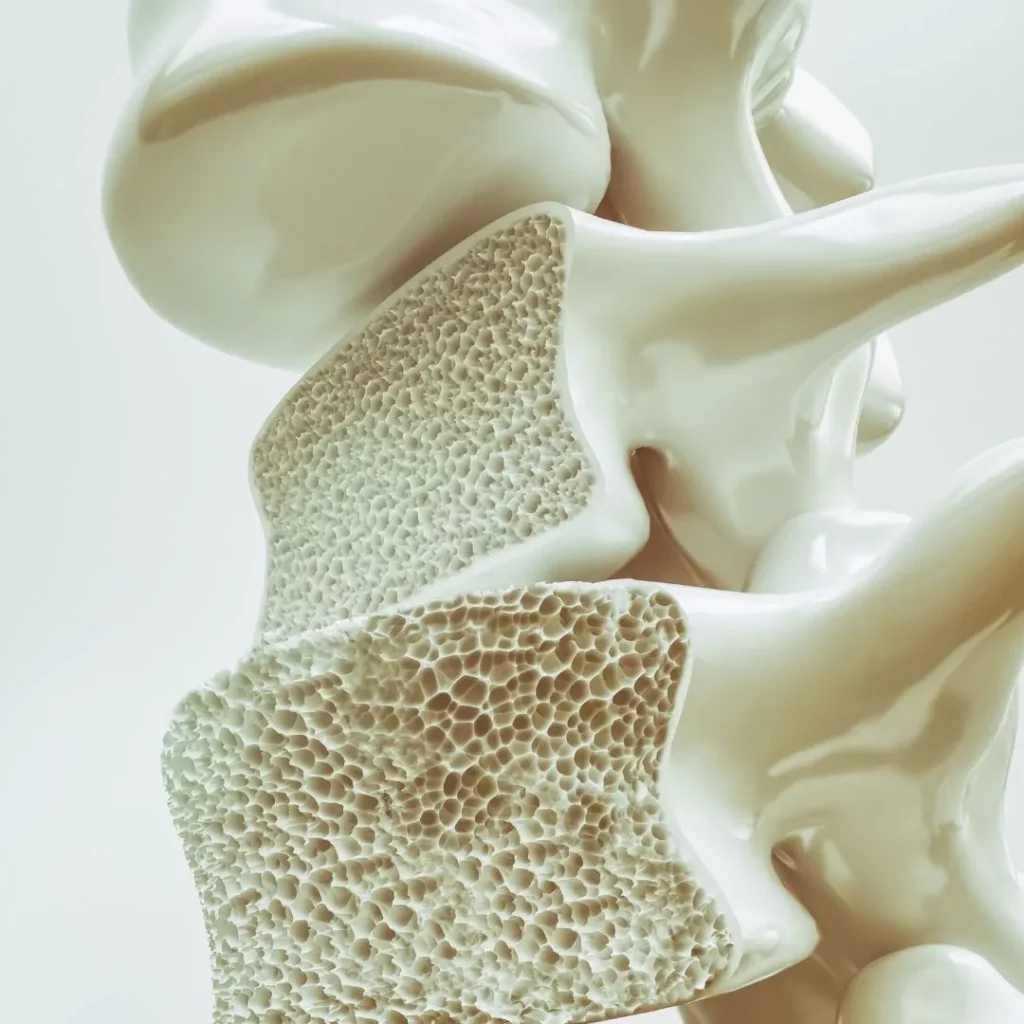

1. What does it mean to have “fragile bones” in spine surgery?

When we talk about “fragile bones” we are mainly referring to two situations:

- Osteopenia: the bone is somewhat weakened, but it does not yet meet the criteria for osteoporosis.

- Osteoporosis: a more marked loss of bone mass and quality, with a higher risk of fractures after minimal impacts or efforts.

In the spine, osteoporosis can cause:

- Vertebral compression fractures.

- Collapse of the vertebral bodies after a fall or even without a clear traumatic event.

- Difficulty for the bone to properly “grip” screws, rods and prostheses used in surgeries such as fusions or deformity corrections.

That is why, in people who need a lumbar or thoracolumbar fusion, a deformity correction or revision surgery, bone quality stops being a minor detail and becomes a central factor in planning.

2. What symptoms can suggest spine and bone problems at the same time?

The symptoms of a spinal condition and osteoporosis can overlap. Some common signs are:

- Low back or mid-back pain that appears after minimal effort or an apparently minor fall.

- Progressive loss of height or increasing thoracic “hump” over time.

- Axial back pain that worsens when standing for long periods.

- Pain radiating to the legs (sciatica, neurogenic claudication) due to spinal stenosis or associated deformity.

- Previous fractures of the wrist, hip or vertebrae after minor trauma.

There are also warning signs that require urgent assessment, regardless of osteoporosis:

- Sudden loss of strength in the legs or arms.

- Difficulty controlling urine or stools.

- Numbness in the groin or genital area.

- Severe pain accompanied by fever, general malaise or unexplained weight loss.

These last symptoms mean you should seek immediate care in an emergency department.

3. How is the spine studied when osteoporosis is suspected?

The assessment of the spine in people with possible fragile bones combines tests that evaluate the structure of the spine and the overall quality of the bone.

3.1. Imaging tests of the spine

- Standing X-rays: they show spinal alignment and help detect vertebral fractures, kyphosis or scoliosis.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI): used to detect disc herniation, spinal stenosis, spinal cord or nerve root compression, as well as changes in the bone marrow.

- CT scan: provides detailed information about the bone and helps plan where to place screws, rods or other implants.

- Dynamic studies (flexion–extension): useful for assessing instability, which is especially important in the setting of weakened bone.

3.2. Specific assessment of bone health

- Bone densitometry (DXA): measures bone mineral density in the spine and hip and classifies the person as normal, osteopenic or osteoporotic.

- Blood tests: may include vitamin D, calcium, phosphorus, kidney function, thyroid and parathyroid function, and in some cases bone turnover markers.

- Assessment of falls and frailty: questions about recent falls, difficulty walking, balance problems or sarcopenia (loss of muscle mass).

In a patient who is going to undergo major spine surgery (for example, thoracolumbar fusion or deformity correction), many guidelines recommend systematic screening for osteoporosis and treating it before surgery whenever possible. This is done to reduce the risk of screw loosening, subsidence of interbody cages and fractures at adjacent levels.

4. Non-surgical treatment options when bone is fragile

Not everyone with osteoporosis and back pain needs surgery. In many cases, the first step is to optimize bone health and conservative management of the spine.

4.1. Treatment of osteoporosis

Drug treatment must be individualized, but usually includes:

- Adequate calcium and vitamin D intake through diet and supplements when needed.

- Antiresorptive drugs (such as bisphosphonates or denosumab) that reduce bone loss.

- Bone anabolic drugs (such as certain stimulators of bone formation) in very high-risk patients or those with complex deformities, when indicated.

The aim is to reduce the risk of fractures and improve bone quality before considering, if necessary, spine surgery that requires long fixations or complex implants.

4.2. Exercise and rehabilitation

Tailored exercise is a key treatment both for osteoporosis and for many spinal disorders:

- Supervised strength and balance programmes to reduce falls.

- Gentle aerobic exercise (walking, stationary cycling, swimming) adapted to the level of pain.

- Specific exercises for paraspinal, gluteal and abdominal muscles, designed by specialized physiotherapists.

In phases of acute pain or after a recent vertebral fracture, rehabilitation must be cautious and progressive, and always prescribed by professionals experienced in fragile bone.

5. When might spine surgery still be necessary in osteoporosis?

Even after optimizing bone health, there are situations in which spine surgery remains the most reasonable option:

- Spinal cord or nerve root compression with progressive neurological deficits.

- Severe deformities that make it impossible to look straight ahead or carry out basic activities.

- Disabling pain that does not respond to a structured conservative treatment.

- Marked vertebral instability or failure of previous instrumentation.

In these cases, the surgeon must adapt the surgical technique to bone quality. In many patients with osteoporosis, approaches that distribute loads more evenly are preferred (for example, fusions with more anchorage points, cemented screws or prostheses designed for fragile bone) instead of techniques that depend on a single screw or isolated implant.

6. Main additional risks of spine surgery in patients with osteoporosis

Spine surgery always carries risks, but in people with fragile bones some of them become especially relevant:

- Loosening of screws or implants: the bone may not hold pedicle screws or interbody cages properly.

- Subsidence of implants into the vertebral bodies: this can alter alignment and make revision surgery necessary.

- Fractures at adjacent levels: when several segments are fused, the vertebrae just above or below may fracture more easily.

- Pseudoarthrosis: difficulty achieving a solid fusion between vertebrae, with persistent pain or instability.

These complications do not occur in all patients, but they are more likely when bone mineral density is low. For this reason, modern guidelines stress the importance of assessing and treating osteoporosis before major deformity surgery or long fusions whenever the clinical situation allows.

7. How can the risk be reduced? Strategies before, during and after surgery

7.1. Before surgery

- Perform bone densitometry and assess fracture risk factors.

- Start or adjust treatment for osteoporosis according to specialist recommendations.

- Address modifiable factors: stop smoking, reduce alcohol consumption, improve nutritional status.

- Take part in a prehabilitation programme (supervised exercise, pain education, respiratory training if extensive surgery is planned).

7.2. During surgery

Some common surgical strategies in patients with fragile bone include:

- Using more fixation points (for example, more levels with screws) to distribute the load.

- Choosing implants designed for osteoporotic bone or using techniques such as cement augmentation of screws in selected cases.

- Avoiding, when possible, removal of bony structures that provide stability if there are less aggressive alternatives.

The specific choice of technique depends on the condition being treated (disc herniation, deformity, pseudoarthrosis, fracture, failed back surgery syndrome) and must be individualized.

7.3. After surgery

- Maintain osteoporosis treatment for the recommended time, unless the medical team advises otherwise.

- Follow an adapted rehabilitation programme, avoiding high-impact exercises in the early phases.

- Watch for new acute back pain, sudden postural changes or loss of height, which may indicate new fractures.

8. Realistic recovery times in patients with fragile bones

Recovery after spine surgery can vary greatly depending on the type of procedure, age, associated illnesses and bone status. In general terms:

- In less invasive surgeries (for example, endoscopic procedures or short fusions at a single level), walking usually starts within the first 24–48 hours.

- Return to office work is often between 4 and 8 weeks, and for physical work between 3 and 6 months, depending on how complex the procedure was.

- In long fusions or deformity corrections, functional recovery is measured in months, and it may take 6–12 months for the final result to stabilize.

In people with osteoporosis, progress may be somewhat slower and require more imaging follow-up to ensure that implants remain well positioned and that new fractures do not appear. It is important to set realistic expectations from the beginning and talk with the medical team about expected sick leave and reasonable temporary limitations.

9. When to go to the emergency department after spine surgery with osteoporosis

After spine surgery, you should seek urgent care immediately if you experience:

- Sudden loss of strength in arms or legs.

- Loss of sensation in the groin area or difficulty controlling bladder or bowel function.

- Severe new-onset pain accompanied by fever or general malaise.

- Very sharp, sudden back pain with a feeling of “cracking” or an abrupt change in posture.

- Significant respiratory symptoms (shortness of breath) after thoracic or thoracolumbar surgery.

These symptoms may indicate complications that require urgent assessment, such as haematomas, infections, fractures or neurological problems.

10. Myths and facts about spine surgery and osteoporosis

Myth 1: “If I have osteoporosis, I can’t have spine surgery”

Fact: osteoporosis increases the risk, but it does not automatically rule out surgery. In many cases, good preoperative treatment and careful planning allow it to be done with a reasonable level of safety.

Myth 2: “Screws always come loose in fragile bones”

Fact: the risk of loosening is higher, but there are techniques to reduce it: choice of implants, cement augmentation in selected cases, more fixation points and improvement of bone quality.

Myth 3: “It’s better not to exercise if I have osteoporosis and back pain”

Fact: tailored exercise is one of the best “medicines” for bone and for the spine. The key is that it is prescribed by professionals and adapted to the clinical situation.

Myth 4: “Medications for osteoporosis don’t affect spine surgery”

Fact: treating osteoporosis can improve implant fixation and reduce the risk of fractures and pseudoarthrosis, especially in major deformity surgeries or long fusions.

11. Frequently asked questions (FAQ)

Can I have a lumbar fusion if I have diagnosed osteoporosis?

In many cases yes, as long as the situation is assessed globally. The spine specialist and, if necessary, a bone metabolism expert will review the type of surgery, the degree of osteoporosis and the treatment needed before and after the procedure. The decision is not based only on densitometry results, but on the overall risk profile.

How long should I take medication for osteoporosis before spine surgery?

There is no single time frame. In some high-risk patients, treatment is started several months before surgery and continued afterwards. The bone specialist will determine the duration depending on the drug used and the fracture risk.

Is a minimally invasive approach safer if I have osteoporosis?

Minimally invasive techniques usually preserve muscles and soft tissues better, which can facilitate recovery. However, safety depends above all on proper indication, the type of fixation and case planning, not just on the size of the incision.

Is lumbar or cervical disc arthroplasty contraindicated in osteoporosis?

Moderate or severe osteoporosis is usually considered a contraindication to replacing a disc with a mobile prosthesis, because it increases the risk of implant subsidence or failure. For this reason, these techniques are reserved for patients with sufficient bone stock and no major contraindications.

What happens if osteoporosis is discovered after I have already had surgery?

In that case, the surgical technique cannot be changed, but steps can be taken to reduce the risk of new fractures or fixation problems: starting treatment for osteoporosis, carefully planning rehabilitation and arranging regular imaging follow-up.

Can I play sports again if I have a fusion and osteoporosis?

In many cases yes, although perhaps not at the same level or with the same type of sport. Low-impact activities such as walking, swimming or cycling are often possible after initial recovery; impact sports or those with a high risk of falls must be assessed case by case with the surgeon and rehabilitation team.

12. Basic glossary

- Osteoporosis: a disease in which bone loses density and quality, increasing the risk of fractures.

- Osteopenia: an intermediate state, with slightly reduced bone density but without meeting criteria for osteoporosis.

- Spinal fusion (arthrodesis): surgery that joins two or more vertebrae using screws, rods and bone graft to eliminate painful motion.

- Disc arthroplasty: replacement of an intervertebral disc with a prosthesis that aims to preserve mobility.

- Pseudoarthrosis: lack of consolidation after a fusion, with persistent abnormal motion between vertebrae.

- Fragility fracture: bone break caused by minimal trauma or even without a remembered fall.

- Densitometry (DXA): test that measures bone mineral density in the hip and spine.

- Spinal deformity: significant alteration of spinal alignment (scoliosis, kyphosis, sagittal imbalance).

References

- North American Spine Society. Evidence-based Clinical Guideline for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Adults with Osteoporotic Vertebral Compression Fractures. 2024. Available online.

- Cho CH et al. Guideline summary review: diagnosis and treatment of adults with osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures. Spine Journal. 2025.

- Al-Najjar YA et al. Bone Health Optimization in Adult Spinal Deformity Patients. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2024.

- Lechtholz-Zey EA et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Effect of Osteoporosis on Fusion Rates and Complications Following Surgery for Degenerative Cervical Spine Pathology. 2024.

- Filley A et al. Influence of osteoporosis on mechanical complications after lumbar fusion. 2024.

- Anderson PA et al. Preoperative bone health assessment and optimization in spine surgery. Neurosurgical Focus. 2020.

This content is for informational purposes only and in no case replaces an individual assessment by qualified healthcare professionals.