- XLIF (also called lateral transpsoas LLIF) reaches the lumbar spine from the side to place an implant between two vertebrae and promote fusion.

- It is often considered when pain and functional limitation are caused by disc degeneration, spondylolisthesis, or stenosis (especially foraminal), and when a well-done conservative plan has not been enough.

- Part of the relief may come from “indirect decompression” (creating space by restoring height), but sometimes that is not sufficient and additional decompression is needed.

- The most characteristic risk is temporary irritation of nerves near the psoas, leading to thigh tingling or hip-flexion weakness. It usually improves, but there are red flags to watch for.

- Recovery varies depending on the number of levels treated, whether additional fixation is used, bone health, and the goals (pain, strength, walking, work).

What XLIF is and why it’s considered minimally invasive

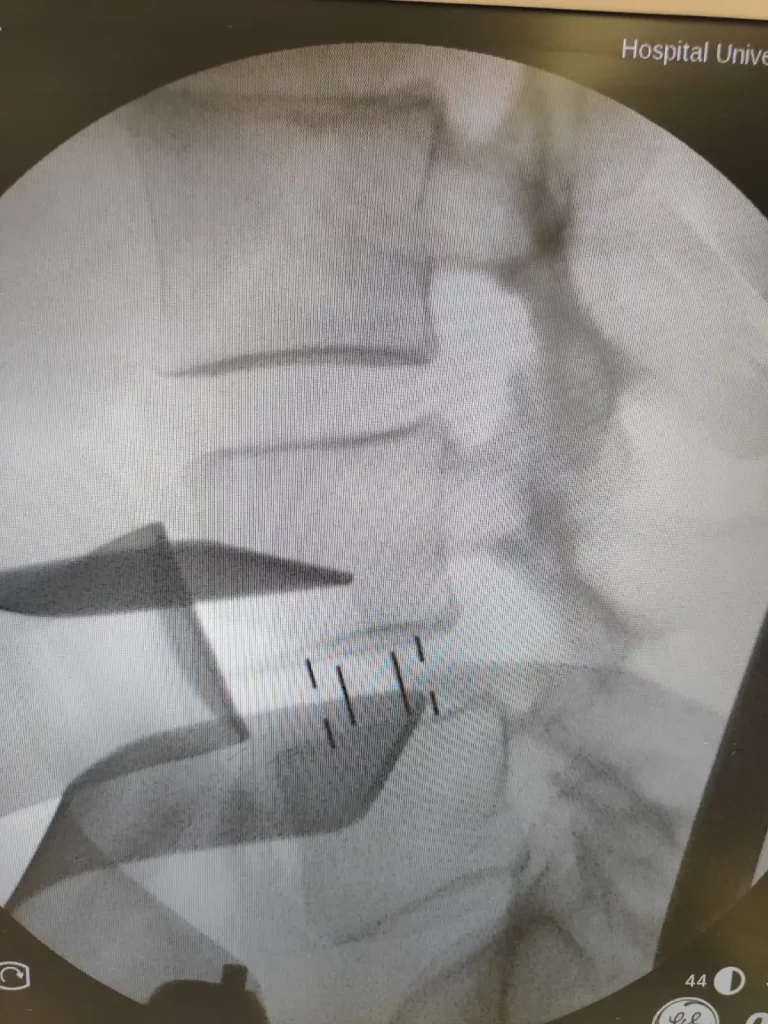

XLIF (Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion) is a lumbar fusion surgery that reaches the intervertebral disc from the side of the body. Instead of going through the back with extensive muscle dissection, the access is lateral, passing through the psoas muscle. The main objective is to place an implant (a “cage” or spacer) between two vertebrae to restore height, improve alignment, and create a stable environment for bone to heal (fusion).

It is considered minimally invasive because, compared with traditional open techniques, it typically uses smaller incisions and less posterior muscle stripping. Still, “minimally invasive” does not mean “minimal impact”: it remains major surgery, with anesthesia, possible implants, and a recovery period.

Signs you may be a good candidate (and why)

There is no perfect universal checklist, but these signs often point toward XLIF once the medical team confirms the diagnosis through exam and imaging:

- Mechanical, limiting low back pain that worsens with standing or toward the end of the day, and does not improve enough with a well-executed conservative plan.

- Nerve-compression symptoms (radiating pain, tingling, heaviness when walking) consistent with stenosis, especially foraminal stenosis.

- Low- to moderate-grade spondylolisthesis or segmental instability that matches your symptoms.

- A degenerated disc with loss of height where restoring space may reduce nerve irritation.

- Selected degenerative scoliosis or mild imbalance where a lateral approach can help correct alignment without an extensive open procedure.

- A need to restore height and alignment to improve posture and load distribution.

- Previously “worked-on” posterior tissues (prior surgery or fibrosis) where avoiding re-entry from the back may be an advantage.

- Good overall health to tolerate anesthesia and rehabilitation, with comorbidities optimized (diabetes, smoking, weight, etc.).

- Realistic expectations: you want better pain and function, understand symptoms may not disappear completely, and accept that recovery happens in stages.

When it usually is NOT the best option

XLIF has anatomical and clinical limitations. It may not be the right technique if:

- There is very severe central compression with major neurological deficit and little room for indirect decompression.

- The level’s anatomy does not allow a safe lateral approach (it depends on the lumbar level and anatomical variants).

- There is an active infection or strong suspicion of an uncontrolled spinal infection.

- Bone quality is very poor and the risk of implant subsidence is high unless an appropriate strategy is planned.

- Pain does not match imaging or another primary source is suspected (hip, sacroiliac joint, predominantly myofascial pain, etc.).

- The goals require a different approach, for example, a very wide direct decompression or correction of a rigid deformity requiring complex osteotomies.

Common symptoms and indications

XLIF is not indicated just because an MRI “looks bad”. It is considered when symptoms affect daily life and match what the tests show. The most common indications include:

- Foraminal stenosis: the nerve is pinched as it exits through the foramen, causing radiating pain, tingling, or cramps.

- Stenosis with neurogenic claudication: walking brings on leg pain or heaviness that improves when you sit or lean forward.

- Degenerative disc disease with loss of height and persistent mechanical pain.

- Degenerative spondylolisthesis with concordant symptoms.

- Selected degenerative scoliosis where restoring height and alignment can reduce pain and improve balance.

How diagnosis is made before considering XLIF

A solid diagnosis usually combines four elements:

- Clinical history: when it hurts, what worsens it, whether symptoms appear with walking, whether pain radiates, and how it affects sleep and function.

- Physical exam: strength, reflexes, sensation, neural tension tests, and assessment of the hip and sacroiliac joint.

- Imaging: MRI for nerves and discs; standing X-rays for alignment and spondylolisthesis; in some cases CT for bone assessment or surgical planning.

- Response to treatments: not “failing for the sake of failing”, but checking whether a properly applied conservative plan changes the course.

One key idea: imaging does not always predict pain. Some people have stenosis on MRI with few symptoms, and others have significant symptoms with less striking findings. That’s why decisions should not be based on a single test.

Alternatives to XLIF

Non-surgical options

When there are no red flags, it often makes sense to try a structured conservative plan first, tailored to your diagnosis:

- Education and gradual activity: understanding the problem and staying mobile usually helps more than rest.

- Physical therapy: glute and core strength, motor control, mobility, walking tolerance.

- Pain management: analgesics matched to your profile, avoiding “miracle” fixes.

- Selected injections: may relieve symptoms in some cases and buy a window for rehab (they are not a “cure” for stenosis).

- Optimizing factors: weight, smoking, sleep, pain-related anxiety, diabetes control, and bone health.

Surgical options (case-dependent)

- Direct decompression (for example, laminectomy or microsurgery): when the main goal is to free the nerve and added stability is not required.

- Posterior-approach fusion (TLIF/PLIF and others): may be preferable if a broad posterior decompression is needed or if the lateral route is not suitable.

- OLIF: another lateral or oblique approach with a different anatomical corridor, with its own pros and cons.

- Endoscopic surgery in selected cases: useful for certain compressions, especially when the goal is decompression with minimal tissue disruption.

Potential benefits and real risks

Benefits we aim for

- Improved pain and function by stabilizing the segment and reducing nerve compression.

- Restoring disc height, which can open the foramen and reduce nerve irritation.

- Less posterior muscle trauma compared with traditional open surgery.

- Partial alignment correction in certain scenarios.

Risks and side effects (without dramatizing, without hiding)

In medicine, honesty means talking about probabilities and ranges, not guarantees. With XLIF/LLIF there are general surgical risks (infection, bleeding, thrombosis, anesthesia complications) and risks more specific to the lateral approach:

- Tingling or numbness in the thigh/groin: from temporary irritation of nerves near the psoas. In a meta-analysis comparing OLIF and XLIF, neuropraxia was more frequent with XLIF, with rates around 21% in XLIF versus 11% in OLIF (studies vary and many symptoms are transient).

- Hip flexion weakness (psoas): usually temporary; you may notice it when climbing stairs or getting into a car. In pooled analyses of lateral approaches in the prone position, meaningful rates of hip-flexor weakness have been described in the early postoperative period, often with progressive recovery.

- Flank or psoas-area pain: due to the access route and tissue manipulation.

- Retroperitoneal hematoma or vascular injury: less common, but important because of potential severity.

- Implant subsidence: more likely with poor bone quality or if the implant is not well supported.

- Indirect decompression may be insufficient: in a series with defined criteria, a small percentage required additional decompression later due to persistent symptoms.

The practical takeaway: XLIF can be an excellent tool, but it requires careful planning, experience, and a well-reasoned plan B if relief is not as expected.

Indirect decompression: the concept worth understanding

“Decompression” does not always mean “removing bone or ligament”. In XLIF, part of the relief can come from restoring disc height and tensioning soft tissues (“ligamentotaxis”), which enlarges the space where nerves travel. This can be especially helpful for foraminal stenosis.

What’s the limit? If the canal is extremely tight, there are calcifications, or compression is very rigid, opening space “from within” may not be enough. In those cases, surgeons may combine XLIF with posterior decompression or choose another technique from the start.

When it makes sense to seek a specialist opinion

- Pain or claudication that limits walking, working, or sleeping despite a well-executed conservative plan.

- Progressive weakness, falls, or clear worsening of function.

- Persistent symptoms with tests showing concordant stenosis or spondylolisthesis.

- After prior surgery if pain changes pattern or returns with new symptoms.

Recovery: realistic timelines and what to expect

Timelines depend on how many levels are treated, whether posterior fixation is added, your bone health, physical condition, and the type of work you do. A practical way to view recovery is in phases:

First 48-72 hours

- The goal is usually to get up and walk as soon as possible, with pain under control.

- You may feel flank discomfort and an unusual sensation in the thigh.

Weeks 1-2

- Walking daily in short blocks is often more helpful than “doing a lot one day and nothing the next”.

- Fatigue and stiffness are common.

- If thigh tingling appears, it often improves over time, but it’s worth keeping track of.

Weeks 3-6

- Many people regain independence for basic daily activities.

- In some cases, desk work can be resumed within this window if recovery is going well and the team clears it.

Weeks 6-12

- Strength and tolerance for standing, longer walks, and household tasks are usually progressed.

- Physically demanding work requires more caution and planning.

Months 3-12

- Function can continue to improve, and fusion healing is a biological process monitored with follow-up.

Important: if pain decreases but confidence in movement does not return, recovery slows. That’s why rehab and education are part of treatment, not an “extra”.

When to go to the emergency department

After spine surgery, some symptoms should not wait:

- Loss of bladder or bowel control, or “saddle” numbness (genital/perineal area).

- New or progressive weakness in a leg (for example, inability to lift the foot) that is worsening.

- High fever with chills and worsening pain, or a wound with heavy drainage.

- Chest pain, shortness of breath, painful swelling of one leg (possible thrombosis/embolism).

- Unbearable pain that does not improve with prescribed medication and is accompanied by neurological symptoms.

Myths and realities

- Myth: “If it’s minimally invasive, there are no risks.” Reality: it reduces certain tissue damage, but major risks remain and other approach-specific risks exist (psoas/plexus).

- Myth: “The MRI decides for me.” Reality: decisions should be based on symptoms, exam, and concordant imaging.

- Myth: “XLIF always decompresses the canal.” Reality: indirect decompression works best in specific scenarios; sometimes direct decompression must be added.

- Myth: “If I feel thigh tingling, something is definitely wrong.” Reality: it can be common and temporary, but there are warning signs (progression, foot drop, rapid worsening) that need assessment.

- Myth: “Fusion means I’ll never move again.” Reality: one segment is fused; the goal is better function and activity tolerance, not immobilization.

Frequently asked questions

Are XLIF and LLIF the same?

In practice, they are used as very similar terms. XLIF is a widely known name for the lateral transpsoas approach. LLIF often refers to “lateral lumbar interbody fusion” as a broader family of lateral techniques.

How long does the surgery take?

It depends on the number of levels, whether posterior fixation is added, and overall complexity. More useful than a single number is asking about total time in the operating room and the plan for pain control and early mobilization.

Will I feel pain on the side?

It’s common to feel discomfort in the flank and in the psoas region at first. It typically improves over the following days with a gradual mobility plan.

Is thigh tingling normal after XLIF?

It can happen due to temporary irritation of nerves near the psoas. Most often it tends to improve. If tingling worsens, significant weakness appears, or there is a clear loss of function, it should be assessed as soon as possible.

Does XLIF work for any lumbar stenosis?

No. It tends to work best when there is room for indirect decompression (for example, a foraminal component and loss of disc height). With very severe central stenosis, it may not be enough without additional decompression.

Can XLIF be done if I’ve already had surgery?

Sometimes yes, and avoiding scarred posterior tissues can be an advantage. But the decision depends on your anatomy, the level, the type of prior surgery, stability, and the clinical goal.

When could I drive again?

When you can move safely, are not taking medication that slows reflexes, and your team clears you. There is no single date – safety comes first.

Will the fusion definitely “take”?

Fusion is a biological process. Factors such as smoking, poorly controlled diabetes, osteoporosis, nutrition, and the type of fixation matter. That’s why planning and follow-up are essential.

What can I do to improve my recovery?

Follow a progressive walking plan, protect sleep and nutrition, avoid smoking, and work with guided rehabilitation. Consistency usually beats occasional “heroic efforts”.

Glossary

- Foramen

- A “window” where a nerve exits the spine. If it narrows, it can cause pain or tingling.

- Stenosis

- Narrowing of spaces where nerves pass. It can be central (canal) or foraminal.

- Spondylolisthesis

- Slippage of one vertebra over another. It can be associated with pain and nerve compression.

- Fusion

- Stable union of two vertebrae so they behave as a single block and reduce painful motion.

- Indirect decompression

- Nerve relief without removing tissue directly, by restoring height and space.

- Neuropraxia

- Mild nerve irritation or injury, often temporary, that may cause tingling or transient weakness.

- Subsidence

- Sinking of the implant into the vertebral bone, more likely with poor bone quality.

- Pseudarthrosis

- When a fusion does not heal as expected. It doesn’t always cause symptoms, but it can lead to pain or implant failure.

References

- Extreme Lateral Interbody Fusion (XLIF): what it is, how it’s done, and who it’s for: https://complexspineinstitute.com/en/complex-spine-institute/en/treatments/extreme-lateral-fusion-xlif/

- Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. NICE NG59 (last updated 2020). https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59

- Emami A et al. Comparing clinical and radiological outcomes between single-level OLIF and XLIF: systematic review and meta-analysis (2023). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37234475/

- Yingsakmongkol W et al. Successful Criteria for Indirect Decompression With Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (2022). https://www.e-neurospine.org/journal/view.php?no=3&startpage=805&vol=19&year=2022

- Petrone S et al. Clinical outcomes, MRI evaluation and predictive factors of LLIF indirect decompression (2023). https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/surgery/articles/10.3389/fsurg.2023.1158836/full

- Limthongkul W et al. Is Direct Decompression Necessary for Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion? (2024). https://www.e-neurospine.org/journal/view.php?doi=10.14245/ns.2346906.453

- Farber SH et al. Systematic review and pooled analysis of complications in prone single-position LLIF (2023). https://thejns.org/spine/view/journals/j-neurosurg-spine/39/3/article-p380.pdf

Important notice

This content is educational and does not replace medical evaluation. If you have progressive neurological symptoms, loss of bladder or bowel control, high fever, or uncontrolled pain, seek urgent care.