Lumbar disc replacement (total disc arthroplasty) can relieve discogenic low back pain in carefully selected patients while preserving segmental motion. It’s not for everyone: the pain source must be confirmed, conservative care exhausted, and contraindications ruled out. Mid-term functional outcomes are comparable to fusion, with potential advantages in motion preservation and less stress on adjacent levels. Recovery is often quicker than people expect, but it requires a structured rehab plan and realistic expectations.

- Not every back pain needs surgery; this technique is for proven discogenic pain after several weeks/months of well-done conservative treatment.

- In appropriate candidates, functional results are similar to fusion and segmental mobility is preserved.

- Main exclusions: multilevel disease, instability, significant stenosis, major deformity, or marked osteoporosis.

- Return to desk work: often 2–4 weeks; manual/physical jobs: 6–12 weeks, with individual progression.

What is lumbar disc replacement?

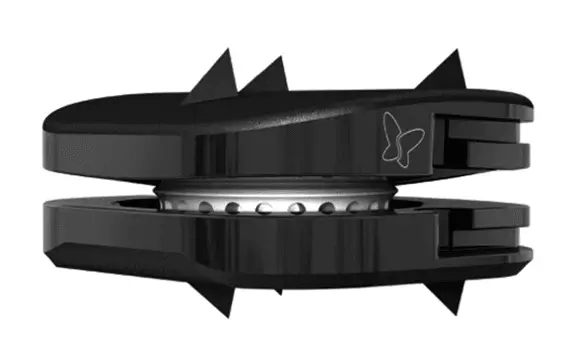

It’s an operation that replaces a degenerated lumbar intervertebral disc with a prosthesis designed to maintain disc height and allow controlled motion. Unlike fusion (arthrodesis), which locks two vertebrae together, disc arthroplasty aims to preserve segment biomechanics and reduce overload on neighboring levels.

Who might benefit?

Typical candidates

- Chronic low back pain of primarily discogenic origin (non-radicular), limiting daily activities.

- Failure of a structured conservative program (therapeutic exercise, judicious analgesia, education and physiotherapy) over several weeks/months.

- Single-level lumbar involvement (with stronger evidence at L4–L5 or L5–S1).

- Imaging and clinical assessment consistent with disc pain, without relevant instability.

Common contraindications

- Symptomatic multilevel disease.

- Clinically significant canal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, marked deformity, or instability.

- Osteoporosis, active infection, tumor, or uncontrolled autoimmune disorders that contraindicate the procedure.

- Prior surgeries that significantly alter the anatomy of the target segment.

Symptoms and red flags

The typical picture is mechanical low back pain that worsens with prolonged sitting or flexion and eases somewhat with walking. Red flags (seek urgent care): progressive leg weakness, fever with severe back pain, loss of bladder/bowel control, or saddle anesthesia.

Diagnosis: confirming the disc is the pain generator

- History and physical exam to rule out facet, sacroiliac, or neuropathic causes.

- MRI to assess degeneration, endplate changes/edema, and to exclude significant stenosis.

- Dynamic X-rays if instability is suspected.

- Additional tests only if they change management (e.g., a diagnostic block when the differential is unclear).

Treatment options

Conservative (first-line)

- Supervised exercise and core strengthening program, with pain education.

- Step-wise analgesia and short courses of anti-inflammatories; avoid chronic opioids.

- Active physiotherapy; passive modalities as adjuncts, not the mainstay.

- Biopsychosocial approach to pain, sleep, and stress management.

Surgical (when appropriate)

- Interbody fusion (arthrodesis): established technique; reduces motion to stabilize and relieve pain.

- Lumbar disc replacement: for selected cases aiming to preserve motion.

- Other decompressions if there is radiculopathy or stenosis (not direct alternatives to arthroplasty when pain is purely discogenic).

Expected benefits and risks/adverse effects

Potential benefits

- Pain relief and functional improvement in selected patients.

- Preservation of segmental motion and a more physiological movement pattern.

- Potentially less load on adjacent levels in the mid-term.

- Relatively quick recovery with small incisions and less soft-tissue trauma.

Risks and complications

- Infection, bleeding, thrombosis, nerve or vascular injury.

- Implant malposition or failure, heterotopic ossification, persistent pain.

- Need for revision or later conversion to fusion.

- Anesthetic and general risks common to major surgery.

Take-home message: results depend on proper indication, surgical technique, and rehabilitation. No surgery guarantees 100% success.

How it’s done and what to expect on surgery day

Arthroplasty is usually performed through a low anterior retroperitoneal approach. After removing the damaged disc and preparing the endplates, the prosthesis is implanted and aligned under imaging guidance. The procedure typically lasts 60–120 minutes, depending on the case. Early mobilization and multimodal analgesia are part of the recovery protocol.

Recovery and realistic timelines

- Days 1–7: walk several times daily, posture hygiene, gentle exercises. Discharge often within 24–48 h.

- Weeks 2–4: gradual return to office/study activities; start structured physiotherapy.

- Weeks 6–8: build strength and endurance; longer driving if pain-free.

- Weeks 10–12: resume low-impact sports; physical jobs require graded return.

Timelines vary with age, fitness, operated level, and job demands. Individual planning prevails.

Practical referral criteria for surgery

- Disabling discogenic pain affecting work/family life despite ≥6–12 weeks of high-quality conservative care.

- Clinical–radiological concordance at a single lumbar level.

- No relevant instability, deformity, or significant stenosis that would favor other procedures.

- Realistic expectations and adherence to rehab.

When to seek urgent care?

- Progressive leg weakness or foot drop.

- High fever with severe back pain.

- Urinary/bowel dysfunction, saddle anesthesia.

- Sudden, incapacitating pain with rapid worsening.

Myths & facts

- Myth: “A disc prosthesis cures any back pain.” Fact: only in confirmed discogenic pain without contraindications.

- Myth: “It’s always better than fusion.” Fact: different tools; fusion remains preferable with instability or deformity.

- Myth: “If I have surgery, I won’t need exercise.” Fact: rehabilitation is essential to consolidate results.

FAQs

Is a lumbar prosthesis better than fusion?

It depends. For single-level discogenic pain, both can yield similar improvements; a prosthesis aims to preserve motion. With instability/deformity, fusion is usually favored.

How long does a lumbar prosthesis last?

Mid- to long-term studies show stable functional outcomes in well-selected patients. Very long-term revisions may be needed.

Can I have a prosthesis if I have sciatica?

If the dominant symptom is sciatica from a herniation compressing a nerve, priority is nerve decompression; arthroplasty is not designed for that scenario.

Can it be done at two levels?

There is experience with one or two levels in selected centers, but indications must be individualized; it’s not for extensive multilevel disease.

When can I drive or travel?

Short drives when pain allows (often weeks 2–4). Long trips are safer after 4–6 weeks with walking breaks.

What if the prosthesis fails?

Some complications may require revision or conversion to fusion. Uncommon with proper indication and technique, but possible.

Glossary

- Discogenic pain: pain generated by the intervertebral disc itself.

- Arthrodesis (fusion): surgery that fixes two vertebrae to eliminate painful motion.

- Disc arthroplasty: replacing the disc with a prosthesis to preserve some motion.

- Heterotopic ossification: bone formation in soft tissues around the implant.

- Spinal canal stenosis: narrowing that compresses nerve roots.

- Spondylolisthesis: slippage of one vertebra over another.

- Pseudarthrosis: lack of solid fusion after arthrodesis.

- Diagnostic block: injection to help identify the pain source.

- Rehabilitation: structured program of exercise and education after surgery.

- Instability: abnormal motion between vertebrae causing pain or risk.

References

- Dr. Vicenç Gilete – Neurosurgeon. https://complexspineinstitute.com/en/institute/#medical_team

- Dr. Augusto Covaro – Orthopedic spine surgeon. https://complexspineinstitute.com/en/institute/#medical_team

- NASS. Lumbar Artificial Disc Replacement – Coverage Policy Recommendations (draft 2024). https://www.spine.org/Portals/0/assets/downloads/PolicyPractice/CoverageRecommendations/Lumbar-Artificial-Disc-Replacement-DRAFT.pdf (2024).

- ISASS Position Statement on Cervical and Lumbar Disc Replacement. Int J Spine Surg. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33900955/ (2021).

- Daher M, et al. Lumbar Disc Replacement Versus Interbody Fusion: Meta-analysis. Orthopedic Reviews. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11062800/ (2024).

- Wen DJ, et al. Lumbar Total Disc Replacements for Degenerative Disc Disease: Systematic Review. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/21925682241228756 (2024).

Disclaimer: Educational content only; it does not replace individual medical assessment. If you have concerning symptoms or questions about your case, consult a healthcare professional.